Multithreading in Blazor WASM using Web Workers

Blazor has multiple rendering models, each with its pros and cons. One of the most popular is Blazor WASM, which enables a highly interactive web application running entirely in the client's browser. But its forte is also its weakness; when you offload the work of running the application to the browser, you must live under its constraints. One of these constraints is that each window in a browser is inherently single-threaded. A way to still do work on multiple threads is by using Web Workers, which are analog to Threads in .NET. In this article, we will go through how to use two of the most prominent Blazor Web Workers OSS libraries; we will show a separate Web Workers implementation that I have created myself which uses the experimental-wasm .NET workload and, in the end, do a little comparison of how each of them performs for a variety of workloads.

Web Workers

Web Workers are defined as a part of the HTML specification. They enable us to run some scripts in the background to avoid blocking the primary thread when we do heavy work. This can be a common problem in Blazor WASM, where the UI can become unresponsive when a heavy workload is executed.

In JavaScript, we can create a worker and listen for messages posted in the worker like so:

let worker = new Worker("my-worker-script.js", { type: "classic" });

worker.addEventListener("message", log)

function log(e) {

console.log("Some message from the worker: " + e.data);

}

The content of the my-worker-script.js file would then define the worker's work. An example could be posting a message to itself, which is what we listen for in the previous code block.

my-worker-script.js

self.postMessage("This was posted from the worker!");

console.log("We can also log to the console directly from here.")

Tewr.BlazorWorker

Tewr.BlazorWorker is one of the first Web Workers abstractions made for Blazor WASM. It is made by Tewr, whom you might also know from the BlazorFileReader library. It uses the Serialize.Linq library to serialize expressions that represent the work that is to be done on the background thread. First, the worker is initialized, which also starts the Blazor runtime from the worker thread. Then, the serialized expression is posted to the worker. The Blazor application, which the worker initializes, listens for messages sent to the worker, and when it sees a new message, it deserializes the expressions and invokes it.

The following is a minimal sample of what you need to do some simple work on another thread. First, you need to install this NuGet package

Tewr.BlazorWorker.BackgroundService

And then add its service to your service collection in Program.cs.

builder.Services.AddWorkerFactory();

Then, on a page, make a setup like this.

@using BlazorWorker.BackgroundServiceFactory

@using BlazorWorker.Core

@inject IWorkerFactory workerFactory

<button @onclick=ExecuteOnTewrBlazorWorker>Execute</button>

<br/>

<code>@result</code>

@code {

private string result = "";

private async Task ExecuteOnTewrBlazorWorker()

{

IWorker worker = await workerFactory.CreateAsync();

var service = await worker.CreateBackgroundServiceAsync<MathService>();

double input = Random.Shared.NextDouble();

double output = await service.RunAsync(math => math.MutliplyByTwo(input));

result = $"{input} * 2 = {output}";

}

public class MathService

{

public double MutliplyByTwo(double input)

{

return input * 2;

}

}

}

The above code sample initializes a service called MathService in the worker and then invokes the method MutliplyByTwo with a random number created on the main thread. The sample is very basic, and obviously, multiplying a number by two is not very expensive. But the idea is still recognizable: Taking some input from the main thread, running some method on the worker thread, and, in the end, returning the result to the main thread.

After going through this minimal sample, my first impression is that it indeed feels pretty minimal. The only part I'm unsure about is the use of Serialize.Linq, which it uses to deserialize and compile the expression every time it is called. Depending on how well the .NET WASM runtime can optimize the generated IL code, this could be expensive.

SpawnDev.BlazorJS.WebWorkers

SpawnDev.BlazorJS.WebWorkers is a newer implementation which is a part of LostBeards project SpawnDev.BlazorJS. It likewise uses Serialize.Linq to serialize the expression that should be evaluated on the worker. But it requires a bit more setup.

Let's see an equivalent to the previous sample but with SpawnDev.BlazorJS.WebWorkers. We first need to add their NuGet package:

SpawnDev.BlazorJS.WebWorkers

Then we need to do a bit of setup in Program.cs.

builder.Services.AddBlazorJSRuntime();

builder.Services.AddWebWorkerService();

builder.Services.AddSingleton<IMathService, MathService>();

await builder.Build().BlazorJSRunAsync();

We add the services needed for BlazorJS to work, a service needed for accessing and creating web workers, and inject MathService as a service. Then, we change a significant part of our Program.cs file. We normally call RunAsync() after building the WebAssemblyHost but here we call BlazorJSRunAsync() instead. This is the primary part that changes the control flow of our Blazor application. The BlazorJSRunAsync method checks whether we are running in the window context, in which case it starts Blazor like usual. Otherwise, it simply idles and listens for messages.

We have updated our MathService a bit by making it implement an interface. This is necessary so the library can create a proxy for the service.

public interface IMathService

{

public double MutliplyByTwo(double input);

}

public class MathService : IMathService

{

public double MutliplyByTwo(double input)

{

return input * 2;

}

}

Then, on some page, we can make our minimal sample again:

@using SpawnDev.BlazorJS.WebWorkers

@inject WebWorkerService WebWorkerService

<button @onclick=ExecuteOnSpawnDevWebWorker>Execute</button>

<br/>

<code>@result</code>

@code {

private string result = "";

private async Task ExecuteOnSpawnDevWebWorker()

{

WebWorker? worker = await WebWorkerService.GetWebWorker();

double input = Random.Shared.NextDouble();

double output = await worker!.Run<IMathService, double>(job => job.MutliplyByTwo(input));

result = $"{input} * 2 = {output}";

}

}

This was a lot more setup than the Tewr sample, even though it seems to use the same core principles. However, that can also be helpful, as it makes certain parts of the internals more transparent to us. This can help library users troubleshoot problems with greater ease.

KristofferStrube.Blazor.WebWorkers

Before looking at how the other solutions worked, I tried to implement my own wrapper for calling .NET through Web Workers. It differs by two key points.

- It does not start a separate Blazor instance in the worker but instead starts a .NET application using the

wasm-experimentalworkload. - It does not use

Serialize.Linqand instead enforces a standard format for a job that needs to be implemented in a separate project.

This makes the implementation a bit more limited. The work being executed by the worker must have a single input and output. Apart from this, you can't use normal Blazor JSInterop in a wasm-experimental project. But if we assume you don't need to use JSInterop for your background job, then this should be fine. So, let's see what it looks like.

You first need to install the wasm-experimental workload

dotnet workload install wasm-experimental

Then, you need to create a separate project in your solution. You can create this project using the standard .NET 8 console template

dotnet new console

To make this a wasm-experimental project, you must adjust the .csproj file to look like this.

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFramework>net8.0</TargetFramework>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<RuntimeIdentifier>browser-wasm</RuntimeIdentifier>

<Nullable>enable</Nullable>

<ImplicitUsings>enable</ImplicitUsings>

<AllowUnsafeBlocks>true</AllowUnsafeBlocks>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="KristofferStrube.Blazor.WebWorkers" Version="0.1.0-alpha.6" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>

Next, we need to add a class that implements the abstract JsonJob class to the wasm-experimental project. The JsonJob class has a single abstract method called Work, where you should implement the work that the job needs to do. The two type parameters of the JsonJob class define the input and output of the job.

using KristofferStrube.Blazor.WebWorkers;

public class MultiplyByTwoJob : JsonJob<double, double>

{

public override double Work(double input)

{

return input * 2;

}

}

To finish the worker part, we just need to update our Program.cs to start our job. Before this, we also checked that it was running in the browser, as this depends on using the interop services for JavaScript, which are only available when running in the browser.

if (!OperatingSystem.IsBrowser())

throw new PlatformNotSupportedException("Can only be run in the browser!");

await new MultiplyByTwoJob().StartAsync();

We then need to take a dependency on the wasm-experimental project from our main Blazor project, and then we are ready to make our minimal sample

@using KristofferStrube.Blazor.WebWorkers

@inject IJSRuntime JSRuntime

<button @onclick=ExecuteOnBlazorWebWorkers>Execute</button>

<br/>

<code>@result</code>

@code {

private string result = "";

private async Task ExecuteOnBlazorWebWorkers()

{

var worker = await JobWorker<double, double, MultiplyByTwoJob>.CreateAsync(JSRuntime);

double input = Random.Shared.NextDouble();

double output = await worker.ExecuteAsync(input);

result = $"{input} * 2 = {output}";

}

}

My solution required even more setup to get the minimal sample up and running, but it also differs a lot, so there might be other gains from this.

Performance comparisons

Now that we have seen three ways to do the same work in the background, let's make some simple benchmarks of how the different solutions perform in various settings. In all these experiments, we will repeat the experiment 1000 times and then take the average of the best 100 results to avoid including outliers. We will also compare the three wrapper implementations with the same work implemented in JavaScript.

All of the following comparisons are also available here if you want to check the code directly or try to reproduce the results on your own machine:

Repository: https://github.com/KristofferStrube/Blazor.WorkersBenchmarks

Live Demo: https://kristofferstrube.github.io/Blazor.WorkersBenchmarks/

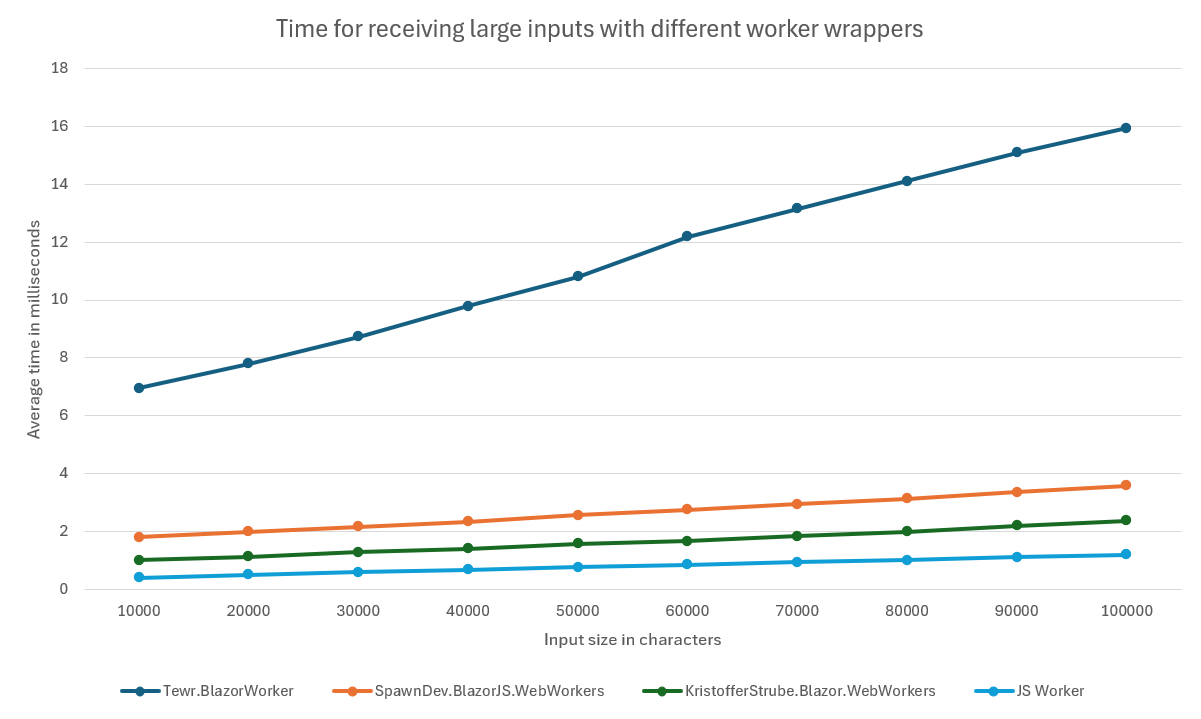

Sending large inputs

It can be expensive to send the parameters needed to run the job. This can be one of the reasons why it might not be worth it to use a worker, as the additional workload of serializing the input would still need to be done on the main thread.

To compare this, we have constructed a simple job that receives a string and always returns the number 42. We intentionally do not use the input to calculate something, as we would then measure the processing time of the input as well.

public class LargeInputJob : JsonJob<string, int>

{

public override int Work(string input)

{

return 42;

}

}

Let's see the result of this small benchmark.

Surprisingly,

Surprisingly, Tewr.Blazor.Worker seems to be much slower than SpawnDev.BlazorJS.WebWorkers. It appears to have a larger overhead from starting some work, but it also grows in running time much faster than the other implementations. If we create a linear fit for the four different sets of measurements, we get the following base overheads and growth rates.

| Worker Implementation | Base in milliseconds | Growth in milliseconds per 10000 chars |

|---|---|---|

| Tewr.BlazorWorker | 5.776 | 1.033 |

| SpawnDev.BlazorJS.WebWorkers | 1.576 | 0.196 |

| KristofferStrube.Blazor.WebWorkers | 0.813 | 0.150 |

| JS Worker | 0.317 | 0.087 |